What is the Purpose of NCEA?

Schools use NCEA pass rates to advertise their success – but it is hard to comprehend what an NCEA qualification actually stands for. Meanwhile, the numeracy pass rate dropped to 40%.

This morning, the NZ Herald published an article looking at NCEA Level 3 pass rates in schools across the country. It emphasises a national decline starting in 2021, whilst highlighting schools that are “bucking the trend” with a higher percentage of NCEA Level 3 graduates in 2023 compared to 2021. These schools’ principals have been interviewed to suggest reasons for the improved data. The answers include employing specialist teachers, allowing pounamu to be worn, allowing study in multiple year levels, employing retired teachers, running a peer-support tutoring programme, famous alumni giving speeches and - most tellingly and paradoxically – dropping NCEA Level 1.

Given the range of answers, it is difficult to see anything else but vague hopes that principals think the policies they implement lead to higher NCEA success. The reason they are guessing is, I believe, that an NCEA qualification is a nebulous reward in a convoluted system. Due to the enormous variety of standards available to gain credits and the many different ways of assessing and grading them, reaching the 80 credits necessary at each level can be done in nearly infinite ways. Being awarded the qualification tells you that a student attempted some forms of educational tasks, and little else. Neither the Education Review Office nor the Education Minister seem to have any confidence in it.

Daisy Christodoulou, Director of Education at No More Marking, recently defined the four purposes of assessment as follows:

To give schools, universities and employers information about an individual student’s level of attainment and capacity for future study / employment (the summative function)

To give teachers, students & parents information about how the student can improve (the formative function)

To give the government and school improvement agencies information about which schools are doing well and are beacons of best practice, and which schools are struggling (the accountability function)

To give everyone information about whether educational standards are improving (the national standards function)

As far as I’m concerned, NCEA assessments individually fulfil a little bit of both function 1 and 2 only. They can be useful to guide students onto courses and pathways, and can be used, although with increasing rarity, as entry requirements for certain classes and degrees. Assessments (especially internals) can also be used by teachers and tutors to give students specific feedback for future improvement. However, the qualification as a whole doesn’t fulfil either of function 1 or 2. They are used for function 3 and 4 erroneously by parents, schools and the media.

What do co-requisite assessment results indicate?

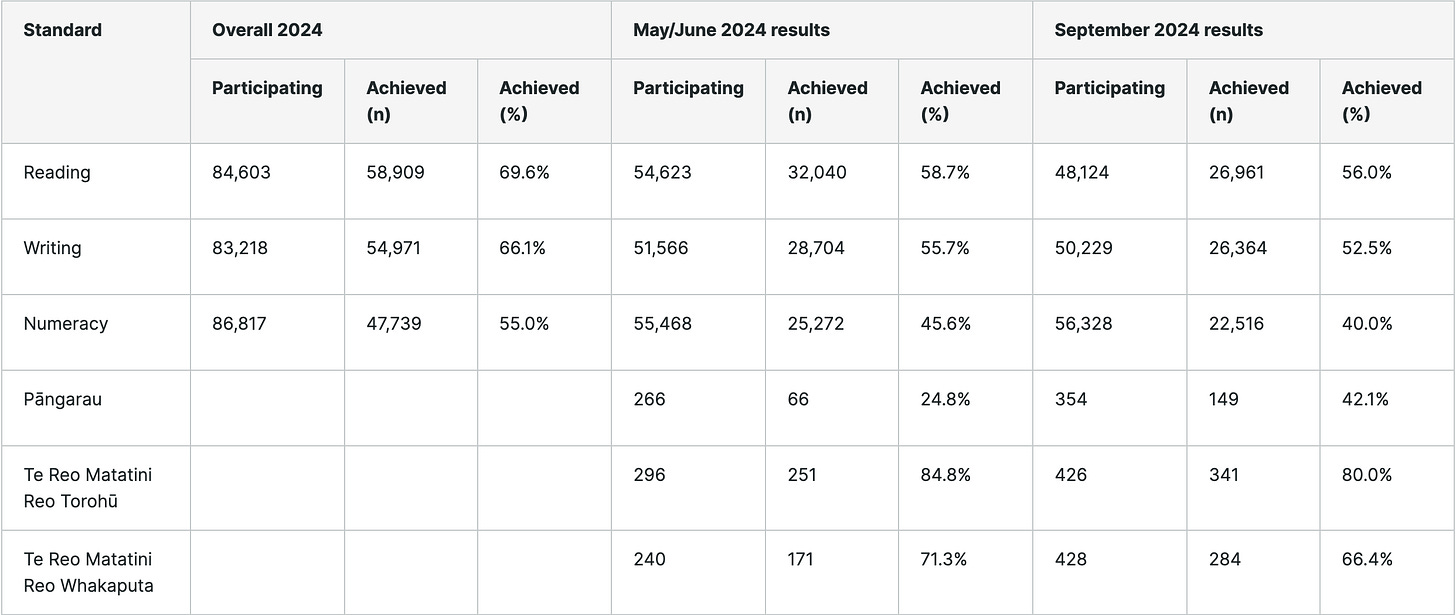

The implementation of co-requisite assessments in reading, writing and numeracy can be seen as an attempt to counteract the increasing meaninglessness of NCEA. It should give confidence that students with a qualification are literate and numerate, although the old flawed pathway of getting these requirements via other standards still exists (and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future). The results from the September assessments were released today:

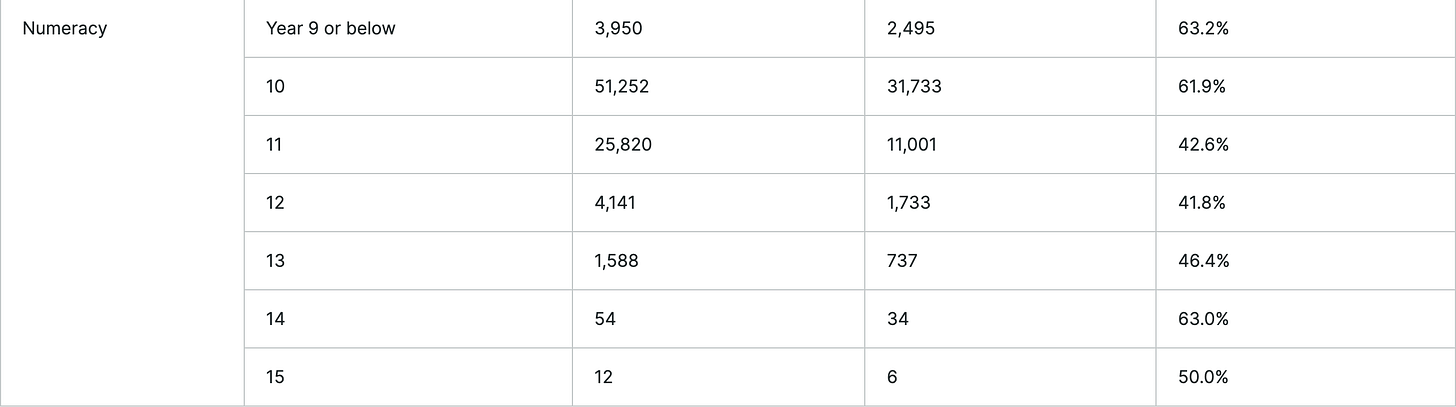

Literacy results were slightly lower in September 2024 but overall better in 2024 than 2023. Numeracy, on the other hand, continues to decline, sliding to just 40%. A break-down of numeracy success in 2024 by year level indicates that senior students are responsible, many of which would have failed this same assessment a third or fourth time:

One of the frustrating aspects of the co-requisite assessments is that schools cannot use these assessments directly to give students meaningful feedback, as their answers are not being released, and the pass requirements remain murky. It is becoming clear that some students are not capable of passing at least one of these assessments, especially if they come from a low socio-economic background. The criticism is valid that baring these students from getting an NCEA qualification is an injustice.

Meanwhile, there is a danger that the co-requisite assessments are used to fill the void for assessment functions 3 and 4. It would be wrong to judge schools based on their numeracy and literacy results because they can selectively exclude students from attempting the assessment. This is not a bad practice – it makes little sense to set up a student to fail in these assessments – but it does lead to better results compared to schools who assess entire year levels systematically. Using the results to judge the educational system as a whole brings the danger of a politically motivated lowering of the assessment difficulty and/or pass requirements.

Despite these flaws, I believe the introduction of the co-requisite assessments is good for our education system because assessments also fulfil a fifth function omitted by Christodoulou: they serve as extrinsic motivation. Politicians, schools, parents and students have started to take literacy and numeracy more seriously in the last two years, which has to be good thing, given that they are foundational skills for other learning.

An NCEA qualification as a whole, however, is a terrible motivational driver. I have worked as a teacher with this system for the last 12 years and I haven’t figured out its purpose. Today was only another stark reminder of what it doesn’t achieve.